How the "foreign intelligence" of Kievan Rus was organized

Published: by .

But truly professional intelligence emerged only in modern times. Some historians believe it originated in the 18th century, others believe it began during the Napoleonic Wars or early 19th century.

Thus, in the Middle Ages, one cannot speak of true intelligence—an organized and targeted structure, operating continuously and systematically, as was the case in the 18th or 19th centuries. On the other hand, such activity was successfully conducted during the Kievan Rus' era, beginning with its emergence on the global political stage in the mid-9th century. Of course, the terms "intelligence" and "intelligence officers" themselves are highly arbitrary for that era. That's why I've put the words "foreign intelligence" in quotation marks in the article's title. Therefore, I use other terms: "spying," "spymen," and in some cases, "scouts," and even "spies," as well as "informants." Therefore, one should also be skeptical of stories about continuous intelligence activities in the Middle Ages, a practice that has been and continues to be common among writers on historical subjects.

The Tale of Bygone Years, the oldest surviving Russian chronicle, compiled at the beginning of the 12th century, reports under the erroneous year 866: “Askold and Dir 1 went to war against the Greeks and came to them… The Tsar [emperor] was at that time on a campaign against the Hagarenes [Arabs]… when the eparch 2 sent him news that the Rus' was going on a campaign against Constantinople [Constantinople], and the Tsar returned. These same [Rus'] entered the interior of the Court 3 , killed many Christians and besieged Constantinople with two hundred ships…” 4

Historians unanimously note that the Rus' attack on Constantinople in the summer of 860 (the date established by Byzantine sources) occurred at a time of great social and political turmoil in the Byzantine Empire. The Arabs were pressing from both west and east. On the eve of Askold's squadron's invasion of the Golden Horn, Emperor Michael led a 40,000-strong army deep into Asia Minor to meet the Arabs. At the same time, he sent almost his entire navy to the island of Crete to combat the pirates, who had become masters of the Mediterranean and were plundering Byzantine merchant ships. The city was left virtually undefended, and in the event of an enemy attack, the townspeople could rely not so much on the small garrison as on the strength of its defensive walls, which no one had previously been able to breach.

Historians have also noted that the gigantic iron chain on numerous floats (which blocked the ships' passage into the Golden Horn) was somehow not taut on that June morning when the Russian ships approached Constantinople. Therefore, Askold's boats entered the bay unhindered. It seems this was the only instance in Byzantine history when, for some unknown reason, the chain was not raised as enemy vessels approached. Even when the Turkish Sultan Muhammad besieged the agonizing Constantinople from all sides in 1453, the Greeks managed to close the entrance to the Golden Horn with a chain… Therefore, there is reason to believe that Askold had accomplices and informants in the Byzantine capital.

This circumstance, as well as Askold's choice of an exceptionally favorable time for his attack on Constantinople, have led scholars to speculate that the Kievan prince had gathered important political and military information before the campaign. The late Nikon Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir knew of the emperor's absence from Constantinople with his army. The section of this chronicle, titled "On the Coming of the Hagarenes to Constantinople," describes the Arab attack on the Byzantine capital. Then, "the Kievan princes Askold and Dir heard of this, marched on Constantinople, and committed much evil." This suggests that Askold was also aware that the Golden Horn was then devoid of Byzantine warships equipped with the dreaded "Greek fire"—metal tubes from which, under high pressure, a flaming mixture of oil, sulfur, and other substances was fired 40-50 meters. This was an incredibly effective weapon in naval combat, which seriously damaged the fleet of the Kievan Prince Igor in 941.

D. I. Ilovaisky suggested that the Rus' knew about the Byzantine army's campaign in Asia Minor and its fleet's expedition to the Mediterranean. M. D. Priselkov wrote about a possible alliance between the Rus' and the Arabs. A. A. Vasiliev believed that the invasion of the empire was planned in advance, suggesting they were familiar with the situation in Constantinople. I. I. Sventsitsky suggested that the 860 campaign was coordinated between Askold and the Bulgarian Empire. D. D. Obolensky concluded that Askold was well informed about everything that was happening in the Greek capital. But we are interested in something else: how and where did the Kievan prince learn of the emperor's departure from Constantinople with his army and the Byzantine fleet's departure for the Mediterranean in June 860?

The renowned Byzantinist M. V. Levchenko also wrote that in mid-9th-century Kyiv, all the important events taking place in Constantinople, and indeed in Byzantium in general, were well-known. Such information could have come from Rus' serving in the imperial guard, as well as from merchants who regularly traveled and sailed along the great route "from the Varangians to the Greeks," which connected the Byzantine and Russian capitals.

True, evidence of Rus' serving in the imperial army and guard appears in sources only from the time of Princess Olga, who ruled Kyiv from 944 to 964, which, however, does not exclude the possibility of such service occurring earlier. However, Russian merchants and ambassadors were indeed frequent guests in Constantinople, as is documented by both Byzantine and ancient Russian sources. The Greek capital even had a quarter, St. Mama's, where a special inn for Russian merchants was located.

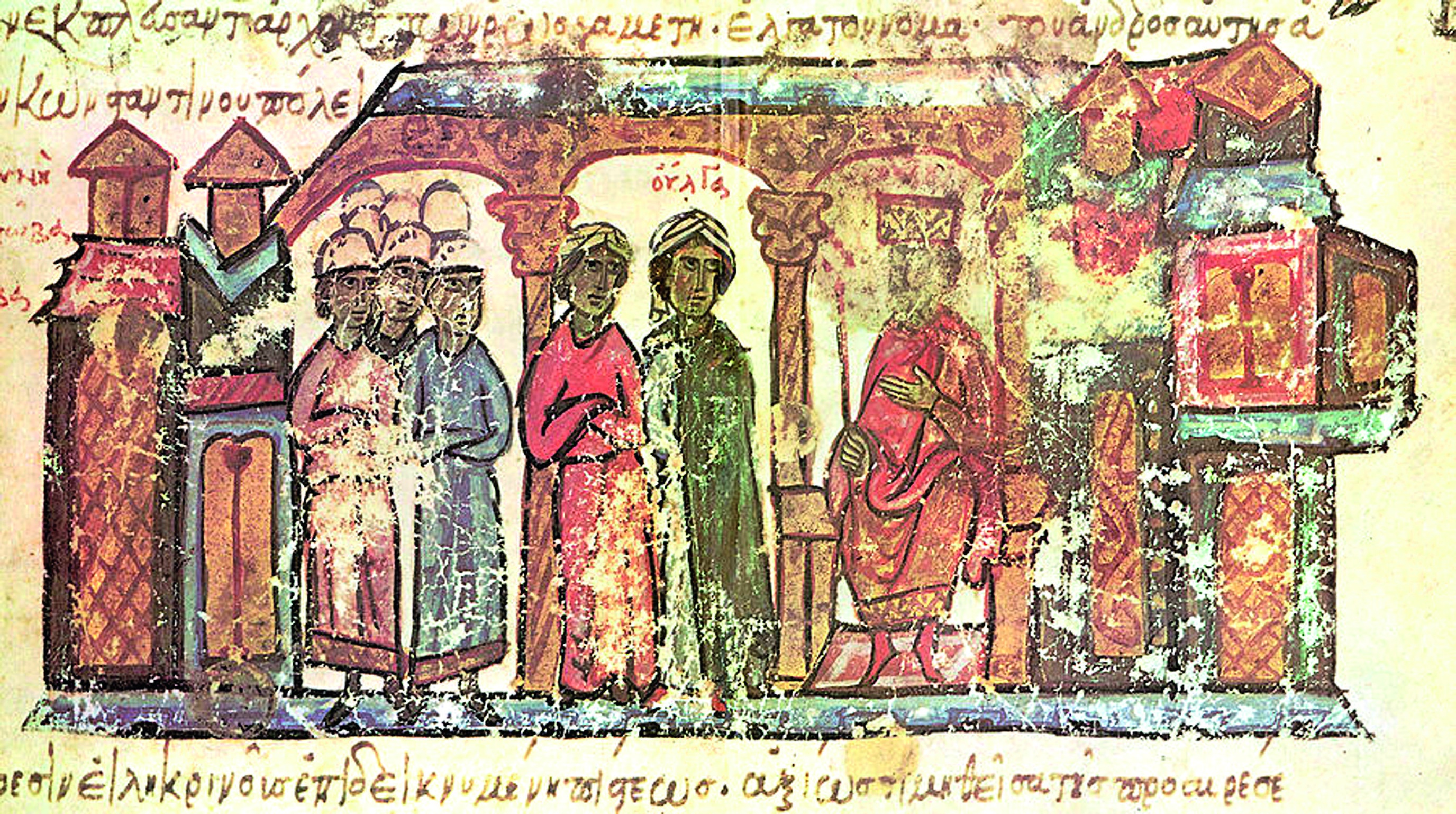

Princess Olga at a reception with Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus. Madrid copy of John Skylitzes's "Chronicle," 12th century.

From the above, one can conclude that a tradition of political and military "reconnaissance" existed in Eastern Slavic diplomatic practice from the very beginning. The surprise of the Rus' attack on Constantinople in 860 for the Byzantine government proves that in this case, too, spies played a role, as Askold's campaign was a carefully planned and, until recently, covert operation. The favorable peace agreement with the Greeks paying a contribution, which the Rus' prince likely secured as a result of the campaign, testifies to the success of the Kievan prince's military undertaking.

Askold was the ruler of the small Kievan principality, located in the Middle Dnieper region. Its economic and military potential was modest compared to Byzantium. The success of the 860 campaign may testify to the significant, perhaps decisive, role of Russian spies in Constantinople and the empire's coastal cities.

The next Rus' campaign against Byzantium occurred half a century later. At the end of the 9th century, Prince Oleg of Kiev, around 882, united the Russian North and South, thus taking the first and decisive step toward creating a pan-Russian state. Fifteen years later, if we are to believe the rather approximate chronology of the Tale of Bygone Years, he made a grand campaign against Constantinople, a brief description of which has been preserved in the chronicle: "Oleg went against the Greeks, leaving Igor in Kiev. He took with him a multitude of Varangians, and Slovenes, and Chuds, and Krivichi, and Merya, and Drevlyans, and Radimichs, and Polyans, and Severians, and Vyatichi, and Croats, and Dulebs, and Tivertsi… And with all these Oleg went on horseback and in ships, and there were 2,000 ships in number. And he came to Constantinople. The Greeks locked up the Court, and the city was shut up." 5

Likely, just as in 860, some Russian spies realistically assessed the internal situation in Byzantium in 907. Prince Oleg and his entourage, one might think, also took into account the empire's international position. After all, Byzantium was experiencing serious difficulties in both its domestic life and foreign policy at that time. The struggle of the major landowners against the emperor was intensifying, and a mutiny broke out in the army. And in 904, the empire suffered defeat at the hands of Bulgaria. The Arab onslaught on the country's southeastern borders continued unabated, inflicting significant blows at sea as well. The Arab fleet captured numerous islands in the Mediterranean, which had recently been dominated by Byzantium. In the same year, 904, the commander Leo of Tripoli, at the head of a powerful Arab squadron, captured the wealthy Greek city of Thessalonica (the Solun of ancient Russian chronicles). Only by mustering all its forces was the empire able to recapture the city and temporarily hold back the enemy onslaught. Byzantium was forced to constantly counter the Arabs with elite military units. It can be assumed that his informants in Constantinople determined the time for the joint campaign of the Russian fleet and land forces. Overcoming the resistance of the few border guards and the sparsely manned garrisons of the Greek fortresses on the Danube, the Kievan sovereign's large infantry force approached the mighty walls of Constantinople, and the fleet suddenly appeared within sight of the guard posts scattered along the banks of the Golden Horn.

This time, the Byzantines managed to raise and tighten the chain, blocking the Russian ships' entry into the bay. Oleg then ordered his small ships to be towed overland on rollers, after which they were launched beyond the chain into the bay. This astonished the Byzantine elite and prompted them to conclude a peace treaty that was very beneficial for the Russian side. 6 Under the terms of the treaties of 907 and 911, Russian diplomats and merchants enjoyed extensive and exceptional privileges in Byzantium, privileges enjoyed by representatives of any other country, not even the German Empire.

Time passed. Five years after the campaign against Constantinople, Prince Oleg died suddenly: either from a snake bite, as Russian chronicles report, or during a campaign in Transcaucasia, as Arab historians and geographers vaguely report. Igor, the son of Rurik, the founder of the dynasty, came to power in Kyiv. He was inferior to Oleg as a statesman and military leader, and this was soon realized in Constantinople. Perhaps this is why the imperial government gradually began to curtail the privileges of Russian merchants and ambassadors in Constantinople, subjecting them to increasingly harsh conditions in inns in the Greek capital and other major cities. The treaties signed by the emperor with Oleg were violated by the Greek side. Therefore, Igor's military action against Byzantium in 941 was not motivated solely by a desire to plunder a wealthy neighbor, as many historians believe. It is more natural to think that Igor and his entourage wanted to restore the privileges of the Russian people in Byzantium, obtained thanks to the treaties of 907 and 911.

Rus' revolted against Byzantium in 941, relying on the friendly neutrality of the Khazar Khaganate, which was at war with the empire and had potential allies in the Ugrians, who were hostile to Byzantium. Furthermore, Igor had formed an alliance with the Pechenegs, a steppe people. He struck a blow to the empire at a time when it was under severe pressure from the Arabs and Ugrians. Its navy was forced to protect the Mediterranean islands from the Arabs, and its land forces were forced to contain their advance in the depths of Asia Minor.

Some historians have seen the Kievan prince's choice of an unfavorable time for the Greeks to attack Constantinople as evidence of his "political intelligence"—just as he had done in 860 and 907. Indeed, all of this could not have been a mere coincidence.

The Rus' campaign against Byzantium in 941 likely surpassed Oleg's similar undertaking in scale. Exaggerating the size of the Kievan sovereign's fleet, our chronicles and Byzantine ones even write of ten thousand ships: "Igor marched against the Greeks. And the Bulgarians sent word to the Tsar [the Byzantine Emperor] that the Russians were marching on Constantinople: ten thousand ships." 7 In reality, Igor's fleet was several times smaller. One Western source (Liuprand) cites a figure of one thousand ships. Simultaneously, a large Russian army also advanced toward the borders of Byzantium…

Nevertheless, the 941 campaign proved a failure for Rus'. It's possible that the Russian prince's informants in Constantinople and the coastal cities of Byzantium misjudged the strategic situation, downplayed the combat effectiveness of its fleet and troops, and, most importantly, provided incorrect information about the condition and location of the formidable imperial ships, which were equipped with exceptionally effective "Greek fire."

In a fierce naval battle, many Russians were burned to death by "Greek fire" 8 , and Igor himself, with a dozen ships, fled to the Kerch Strait, according to the Byzantine historian Leo the Deacon, a contemporary of the war. The infantry also returned to Russia, having suffered defeat.

Less than three years had passed before Igor, thirsting for revenge, had gathered an even larger army and navy and once again marched on Constantinople. Tellingly, the emperor learned of this from his informants in the coastal Crimean city of Kherson: "Hearing of this, the Korsunites sent to Roman with the words: 'Here come the Russians, countless ships, covering the sea.'" 9 . On the Danube, Igor was met by an embassy from Emperor Roman, who proposed peace. It is likely that the Russian prince learned from his informants in Byzantium that a fiery Greek fleet awaited him at the mouth of the Danube, and that imperial legions were hastening there… After lengthy negotiations, peace was signed in 944 in Kiev, where the imperial embassy had arrived. The agreement proved less advantageous for Rus' than Oleg's treaties.

The text of Igor's treaty with the Greeks of 944, included in the Tale of Bygone Years, contains words attesting to the visit of Russian spies to Constantinople. The Byzantine government demanded that Igor require ambassadors and merchants from Rus' to carry credentials stating the purpose of their visit: "If they arrive without credentials and fall into our hands, we will keep them under surveillance until we notify your prince. If they do not surrender to us and resist [arrest], we will kill them, and let their death not be held against your prince. If, however, they flee and return to Rus', we will write to your prince, and let them do whatever they wish." 10

The text of the treaty indicates that agents of the Kyivan prince, when caught red-handed, often refused to surrender to the Byzantine police and offered armed resistance. The practice of sending spies from Rus' to Byzantium was likely widespread, since a major interstate treaty specifically mentioned them and stipulated the practice of detaining such agents.

Let me try to answer the question: who performed the role of these peculiar scouts in Rus' and in the medieval world in general? Historians have long believed that they were most often merchants who traveled the world, gathering political and military information along the way. Or they were given special assignments. It's telling that in 1043, when Yaroslav the Wise's war with Byzantium began, its authorities ordered the arrest of all Russians in the country, primarily in Constantinople. The Greek government was wary of releasing Russians, many of whom possessed important information about the state of the empire, its army, and navy.

Political and military "intelligence" was similarly carried out by those entrusted with ambassadorial functions. Finally, sources contain ample evidence that missionaries and travelers collected information about the countries they visited. The accounts of Arab, Persian, and Western European travelers provide a certain understanding of Rus' in the 9th and 10th centuries, including the state of its army and navy. Russian pilgrims to holy sites in the Middle East also brought back important information.

Akimov I.A. Baptism of Princess Olga in Constantinople.

After Igor's violent death in the land of the Drevlians in the autumn of 944, his wife Olga succeeded him to the Russian throne. She favored peaceful methods of foreign policy. For the first time in the history of the Old Russian state, its sovereign traveled to the capital of Byzantium not at the head of an army and navy, but with a peace embassy.

Historians have long noted the deceptive simplicity of the Tale of Bygone Years' account of Princess Olga's visit to Constantinople. The chronicler ignored (or was unaware of) the painstaking and lengthy work of the Russian embassy service that supported this trip. It must have been preceded by a thorough investigation of the political situation in Constantinople—most likely by Russian merchants in Byzantium and possibly by Russian mercenaries in the imperial guard.

It's also easy to understand that the princess simply couldn't organize an embassy to Byzantium without fulfilling the numerous formalities that were so prevalent in imperial foreign policy ceremonies. Furthermore, Olga's very presence in Constantinople with her large retinue could have been used to gather political information.

Sources suggest that during Olga's stay in Constantinople, the Russo-Byzantine treaty concluded between Igor and the emperor in 944 was renewed. However, it is unlikely that the privileges granted to Russian merchants in Byzantium were increased. Olga's hopes of becoming related to the emperor by marrying her son Svyatoslav to one of the daughters of Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus also failed to materialize.

Some church historians believe that, following the partial success of negotiations with the Byzantine Emperor, the Russian princess, in opposition to him, sought to establish a church organization in Rus' with the help of the German sovereign. However, this leaves open the question of why Olga was solemnly baptized in the Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, with the Byzantine Emperor himself serving as her godfather. Furthermore, the arrival of the German missionary Adalbert in Rus' in 960 or 961 was met with hostility by the Russians, and the hapless candidate for the Russian bishopric was forced to return home empty-handed.

In recent years, historians have increasingly come to believe that when Olga sent her representatives to the German Emperor Otto I in 959, her primary goal was to familiarize herself with the situation in the country, with whose ruler she intended to establish friendly relations. It seems natural to think that the Russian embassy was tasked with studying the political situation in Germany in order to assess the prospects for concluding a Russo-German treaty of "peace and friendship," as our chronicles usually refer to alliance agreements. The results of this, quite possible, familiarization likely convinced the princess of the undesirability of establishing systematic interstate relations with the German Empire, because neither Olga nor her son Svyatoslav, who succeeded his mother on the Kievan throne in 964, ever took further diplomatic steps in this direction.

Svyatoslav Igorevich (reigned 964-972) went down in history as a successful military leader and brave warrior, who preferred to resolve foreign policy issues through the use of military force. His main rivals in Europe were the Byzantine Empire and Khazaria. Before confronting them, the Russian prince decided to conduct reconnaissance in force. The Kiev chronicler, in his characteristic lapidary style, described this event for the year 964: “Svyatoslav went to the Oka River and the Volga, and met the Vyatichi 11 , and said to the Vyatichi: “To whom do you give tribute?” They answered: “To the Khazars – we give a schelyazh from a plow!” 12 As the expert on the Khazar problem A.P. Novoseltsev wrote, the campaign of 964 was obviously a political sounding in that region 13 . Having determined the borders of the Khazar Khaganate, assessed its army and familiarized himself with the general situation in the Volga region, Svyatoslav quickly moved against the enemy and defeated him. Four years later, the regiments of the Kiev prince finally liquidated the Khazar state. As V. T. Pashuto wrote, the castles at the mouths of the Volga and Don were knocked down, and land routes were cleared for Russian merchants to the countries of the South and the East.

But Khazaria was not Rus''s main enemy in the east and south. Svyatoslav encroached on Byzantium's zone of influence in the Danube region—Bulgaria, likely realizing that doing so would bring him into conflict with the empire. From 968 to 971, he waged war against Byzantium and was ultimately forced to abandon Bulgarian lands along the Danube.

During the Russo-Byzantine Wars, both sides repeatedly resorted to "external intelligence." But while the Russian prince preferred reconnaissance in force, the emperor, according to Leo the Deacon, used spies sent into the Russian camp.

Leo the Deacon writes that the Greek sovereign ordered "to send people dressed in Scythian 14 clothing, speaking both languages, to bivouacs and areas occupied by the enemy, so that they would learn about the intentions of the enemy and then report them to the emperor" 15 . It is natural to assume that similar scouts were also sent by Svyatoslav to the location of the Byzantine troops.

In conclusion, it's worth telling the story of Princess Olga's use of a spy during the Pecheneg siege of Kyiv. Svyatoslav was in Bulgaria at the time, where he had withdrawn his army, and a small garrison remained in the city. The Greeks incited the Pecheneg khans against the capital of Rus' in order to force the Russian prince to abandon the Danube region. In 968, the Pechenegs approached Kyiv and laid siege to it. Famine began in Kyiv, and reinforcements from Svyatoslav still did not appear within sight of the Russian outposts. Finally, they saw some people gathering on the opposite bank of the Dnieper, but contact with them was impossible.

The Tale of Bygone Years vividly and emotionally recounts the events of those days: "And the people in the city began to grieve, and said: "Is there no one who could cross to the other side and tell them: "If you do not approach the city in the morning, we will surrender to the Pechenegs!"

Then a young man volunteered to make his way to the people standing on the other bank. "He left the city, holding the bridle, and ran through the Pecheneg camp, asking them, 'Has anyone seen a horse?' For he spoke Pecheneg, and they accepted him as one of their own." The young man safely reached the bank of the Dnieper, jumped into the water, and swam. Convinced that the young man had deceived them, the Pechenegs rushed after him, shooting at him with bows, but to no avail.

Before us is a classic example of the Middle Ages of actively studying the enemy's forces using military cunning.

The scout was adequately prepared: he spoke the Pecheneg language and was able to swim across the wide Dnieper River near Kyiv. It turned out that Svyatoslav's voivode, Pretich, was stationed on the other side of the river with his army. He managed to alleviate the besieged, and soon Svyatoslav returned home and drove the Pechenegs back into the steppe.

This is how, in the light of Russian and Byzantine sources, “intelligence” activities in Rus' appear, serving the active diplomatic and military policies of its princes – from Oleg to Svyatoslav.

Notes

- 1. In reality, Askold and Dir reigned in Kyiv not simultaneously, but successively, one after the other: first Askold, and from the late 70s to early 80s of the 8th century, Dir. Therefore, it is likely that Askold alone marched against Constantinople.

- 2. An official appointed by the emperor who was entrusted with defending Constantinople from enemies.

- 3. The Golden Horn Bay, which washed the shores of the capital of Byzantium.

- 4. The Tale of Bygone Years. St. Petersburg. 1899. Page 149. Here and further the chronicle is cited from this edition in D.S. Likhachev’s translation into modern Russian.

- 5. The Tale of Bygone Years. P. 152.

- 6. Oleg's treaties with Byzantium in 907 and 911 are the first known international agreements of the Old Russian state, which was still in the process of formation. They were written in Greek. Russian translations of these treaties were included in the Tale of Bygone Years at the beginning of the 12th century (Tale of Bygone Years, pp. 154-156).

- 7. The Tale of Bygone Years. P. 158.

- 8. The chronicler testifies: “Theophanes [the Greek admiral] met them in boats with fire and began to blow fire with trumpets at the Russian boats” (Tale of Bygone Years. P. 159).

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. The Tale of Bygone Years. P. 160.

- 11. East Slavic tribes that lived in the area between the Oka and Volga rivers.

- 12. The Tale of Bygone Years. P. 168.

- 13. Novosel'tsev L. P. The Khazar sovereignty and its role in the history of Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Moscow, 1990, p. 225.

- 14. The Byzantines called the Rus' Scythians or Tauroscythians.

- 15. Leo the Deacon. History. Moscow, 1988, p. 58.

Comments