On January 18, 2010, writer Vladimir Karpov died. He took plots for his books from life at the front

Published: by .

According to the precepts of Paustovsky

The conversation that junior research fellow at the Institute of History of the USSR Academy of Sciences Vera Loginova conducted with Karpov as part of the work of the Commission on the History of the Great Patriotic War turned out to be one of the most unusual among the archival transcripts with stories of heroes. As a rule, the memoirs of those awarded the Gold Star of the Hero were recorded months after the Decree on the award was issued. At the time of the publication of the decree, Karpov was in Moscow, studying until September 1944 at the Red Banner Higher Intelligence Courses for the Improvement of Officers of the Red Army.

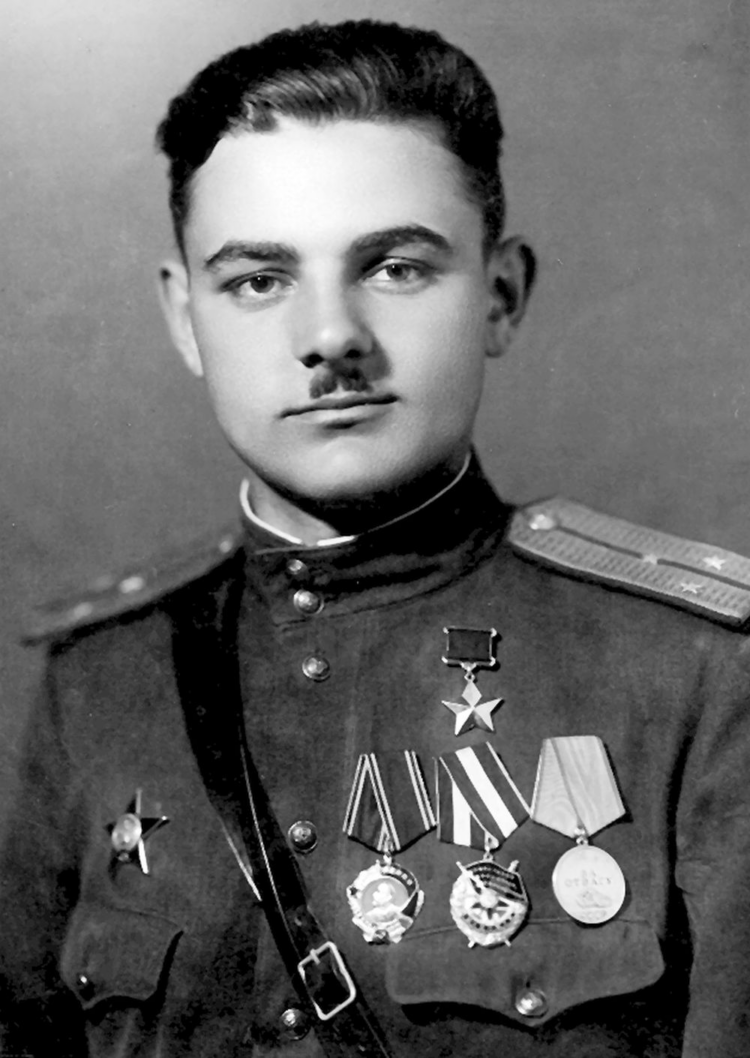

V.V. Karpov (1922-2010). Photo: G. Vailya. Scientific archive of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The decree on the award was dated June 4, 1944, it was published in the central newspapers on Tuesday, June 6, and already on Thursday, June 8, the brave intelligence officer appeared at the Commission on the History of the Great Patriotic War. In his fictionalized book of memoirs, "The Great Life," published a year before his death, in 2009, Karpov colorfully describes how he learned about his Hero's Star from the Izvestia billboards that had just been pasted up that morning on a street billboard, how he happily kissed the grandmother who was putting up the billboard, and how he doubted whether it was he who had been awarded, since the decree listed "Lieutenant Vladimir Vasilyevich Karpov," and he was already a senior lieutenant. "After classes, I went to the awards department of the Supreme Council, showed them Izvestia and asked them to clarify – maybe it was me in the Decree. They treated me with distrust: it was strange, the Decree had just been published and immediately the recipient of the award showed up: "Leave your address and phone number, we will check and let you know." A week later, an invitation came to the Kremlin to receive the award" 2 .

The Commission on the History of the War was closely connected with the Awards Department of the Supreme Council, and the intelligence officer who had come there even before the award was presented to M.I. Kalinin was sent to talk to Vera Loginova.

In the nearly 800-page memoirs of 2009, there is no mention of the conversation at the Commission on the History of the Great Patriotic War at all, although Karpov personally edited the transcript of the conversation in 1944. It was then that photographer G. Weil took two photos of him with the Hero's Star (in a cap and without a headdress), which are also stored in the Scientific Archive of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences 3 .

Transcript of interview with V.V. Karpov. Photo: Scientific archive of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Both the transcript of the conversation and the story of military exploits in his later memoirs should be assessed with an allowance for the author's rich imagination and his combat experience as an intelligence officer. While studying at the Literary Institute after the war, Karpov remembered well a characteristic statement by Konstantin Paustovsky, whose seminar he had attended:

"- What shortcoming do you consider forgivable?

– Excessive imagination" 4 .

At 21 years old, as the transcript shows, Senior Lieutenant Karpov not only had an “excessive imagination,” but also mastered the art of legend-making, which a real intelligence officer cannot do without.

From the Tashkent punks

The future writer's biography before his appearance at the front was not easy, and there was something to hide in the conversation with Vera Loginova. The 21-year-old Hero of the Soviet Union had already been convicted twice. In his 2009 memoirs, he claimed that he "never told anyone in my later life about his first criminal case… I hid the indecent zigzag in my youth" 5 . In fact, in the 1944 transcript, Karpov talks about the "indecent zigzag" at the very beginning. There was no way to evade it: in the personal data preceding the transcript, it is stated that he was "a member of the party since 1943" and "was in the Komsomol since 1938, but was expelled" 6 .

And here's why they expelled him: in Tashkent, where the Karpov family had lived since 1929, 16-year-old Volodya "was arrested in 1938 and tried as a member of a gang of repeat offenders. Of course, I was not a daily participant in these cases. But it so happened that I was in a restaurant with a friend, we didn't have enough money, we left the restaurant and a suitcase was taken from a passerby, we were tried. Since I was not an active participant in this case, I was given a suspended sentence of one year… I only spent a month and a half under investigation" 7 .

In his 2009 memoirs, the writer wrote about this incident in more detail and in a significantly different way. According to him, he first visited a restaurant in Moscow in 1945, while studying at the Higher Intelligence School of the GRU General Staff. And before that, "I had never been to a restaurant in my life. I had never had the chance to go to Moscow or Tashkent: school, prison, war, what restaurants!" And as a teenager, Volodya really did get along with the Tashkent punks, and from the age of 14 "he took part in several simple robberies at "gop-stop" on the evening streets." Money appeared, with which he "enjoyed sweets, cakes, chocolate, ice cream."

Defense of Moscow. Scouts go for a "tongue". 1942. Photo: RIA Novosti

The young robbers were indeed arrested for the stolen suitcase, but if we are to believe Karpov's memoirs, the case was also political. In a dark alley, the suitcase was taken from a woman who turned out to be the third secretary of one of the Tashkent district party committees. Volodya's participation was actually active: he and his friends "held the woman for several minutes and, without causing her any harm, let her go" until their accomplice ran off with the suitcase. Then they broke into the suitcase, divided the money found in it, and immediately began to spend it, "went into a grocery store and bought a soft, rich bun. I ate it with pleasure, and life seemed wonderful to me!" 8

To the front to atone for guilt

Life really turned out to be wonderful then: the case was hushed up (according to the memoirs, one of the young robbers turned out to be the son of a prominent NKVD officer). Volodya set out on the path to correction, graduated from school with flying colors, became a boxer known to all of Tashkent, the middleweight champion of Uzbekistan, and in 1939 entered the Tashkent Infantry School. But shortly before graduation, on February 5, 1941, he was arrested again and on April 27 of the same year, by the verdict of the military tribunal of the Central Asian Military District, he was sentenced to 5 years of imprisonment and 2 years of disenfranchisement.

The arrest left the cadet perplexed: "When I was imprisoned, I myself did not know what exactly it was for." And long after his imprisonment, when the conviction had long since been expunged for his front-line distinctions, Vladimir Vasilyevich often got confused in his testimony about the reasons for this arrest – he mentioned, in particular, a conversation with fellow cadets about how after Lenin there were figures in the party who were greater than Stalin. In the 1944 transcript, he had to resort to legend: it was inappropriate to mention the slander against the leader at that time. And this is what Karpov said: "My anti-Soviet agitation was expressed in a letter to one girl. At that time, the Sedovites were drifting, they were awarded the title of Heroes of the Soviet Union. I wrote: these are happy people, what did they do special? They drank all the vodka, went for a walk, and they were made Heroes" 9 .

Award sheet on conferring the title of Hero of the Soviet Union to V.V. Karpov.

As we can see, Stalin is not even mentioned here. The real reason for the arrest of cadet Karpov is, in all likelihood, connected with the first person of the state. In his petition to Kalinin on September 19, 1942, asking to be sent to the front from the camp, he writes that he "expressed himself offensively towards the leader of the peoples" 10 . The future author of the two-volume "Generalissimo" in his youth showed himself to be anti-Stalinist, for which he was sent to Tavdinlag in the Sverdlovsk region, and then to Sverdlovsk itself to the camp during the construction of the artillery plant No. 8 evacuated there. There he became a foreman of prisoners, and in December 1942 the opportunity arose to go to the front.

Reforging in the German rear

Hero of the Soviet Union Karpov was at the front for only a year, from January 1943 to January 1944, but how well and successfully he fought! Next to the Hero's Star and the Order of Lenin in the aforementioned archival photographs, we see the Order of the Red Star and the Order of the Red Banner, as well as the medal "For Courage". Vladimir Vasilyevich tells about his exploits as a scout in the transcript close to the texts of the corresponding award sheets, adding colorful details designed to impress the junior research fellow Loginova. For example, this detail: "I was a boxer, I can silently kill a man with just one fist. There are about 50 Germans, we will kill them at night once, once" 11 . The second sentence, however, was crossed out by the senior lieutenant when editing the transcript. And at the very end of his story he added statistics: “On my account: 158 killed Germans, 17 stabbed to death, 79 brought back alive” 12 .

The future author of the novel "Take Alive!" also briefly described his initial stay in the penal company, which was supplemented in his 2009 memoirs with a capacious testimony: "Nine people out of four platoons survived – those who ran back to their trench" 13 . And in a more detailed, sometimes colorful, way, he told in the transcript about his path as a scout in the 629th Infantry Regiment. Already at the beginning of his front-line biography, he received the medal "For Courage" and a certificate of expungement of his criminal record. The very first trip behind enemy lines for a "tongue" turned out to be a success for the former prisoners: "There were 12 of us in the regiment, all good guys. We sat together, lived together, were very friendly and all became scouts. They didn't tell us that they hadn't taken a tongue for 6 months, they just said, "Bring us," and that's it" 14 .

And on January 27, 1943, they brought in the "tongue." Having overcome eight rows of barbed wire and minefields, Private Karpov and his comrades penetrated into the Nazi rear. "I see the Germans sleeping in the dugout. I stabbed five of them, they never woke up. I felt the heart of the dead man with my hand – it was done. I woke one up. He jumped up. I was covered in blood, like a butcher. I was wearing a white camouflage suit, the blood was especially visible on it, he was all spattered with blood, such an unpleasant smell. We took this one I left alive, went out through the passage, took the documents of the others. For this I received the medal "For Courage" 15 . In May 1943, the recent prisoner was already wearing the shoulder straps of a junior lieutenant.

Commander of the 629th Rifle Regiment, Colonel A.K. Kortunov.

Rescue of Commander Kortunov

The brave scout, who had to "go to the rear on command assignments" 38 times, was supported by the sensible and fair commander of the 629th Infantry Regiment. He was invariably there throughout Karpov's life at the front, Alexei Kirillovich Kortunov, the future multiple Union Minister, who made a significant contribution to the development of the Soviet oil and gas project 16 . He repeatedly nominated the young scout for high awards, and for his distinctions in the battles near Dukhovshchina in the Smolensk region, on September 21, 1943, he signed the initial submission for the assignment of the title Hero of the Soviet Union. On October 18, the award sheet was finally formalized with the signature of the commander of the Kalinin Front, A.I. Eremenko.

The hero received his award only 7.5 months later, but the time for his presentation for the title was well chosen. By September 19, 1943, the Smolensk cities of Dukhovshchina and Yartsevo had been liberated, a notable success on this section of the front, and Lieutenant Karpov's real combat merits by that time were undeniable. Including saving the life of regiment commander Kortunov in September 1943 near the village of Basino in the Dukhovshchina district (in Karpov's transcript, Vasino; in Kortunov's presentation, Vasilevo). In the presentation for the title of Hero we read:

"When I, the regiment commander in the area of the village of Vasilevo in the Dukhovshchinsky district of the Smolensk region, found myself in a difficult situation with a small group of fighters, due to the enemy's superior forces launching a counterattack, Comrade Karpov, risking his life, broke into the enemy's flank with a fight, personally killed up to 25 Germans with his machine gun and ensured both the repulse of the counterattack and the capture of a strong point in the village itself" 17 .

Karpov himself dramatically tells the story of rescuing the regiment commander from a difficult situation; his story already shows the makings of a future writer: "They told me roughly where the regiment commander ran. If you crawl straight ahead, you need to crawl through a clear place, and if you crawl through the bushes, then the Germans are walking around here. My entire camouflage suit and quilted jacket were wet, because I was terribly hot from the tension. I see that the regiment commander, his adjutant and orderly are there. I barely crawled to them. When I crawled, I lost the disk from my machine gun. I crawled up, the regiment commander says:

– What are you hanging around here for? 18

Kortunov, according to Karpov, sent him with a report to the division headquarters. "I threw down my machine gun and crawled with only one knife. I crawled for about two hours. I didn't reach the ridge by about 15 meters, such indifference overcame me from fatigue, I thought: "If only they would kill me", I stood up and walked at full height. So the enemy tore everything around me apart, but I still got there safely, delivered this report. They quickly sent reserves to help us, I rested and still went to rescue the regiment commander. I crawled not directly, but along the bushes. At that time, the German discovered me, babbling: "Rus, Rus". I began to shoot back. Then the reserves that arrived drove them out. I counted, there were 25 killed Germans around me" 19 .

…A year after this transcript, on June 24, 1945, Vladimir Karpov will be the standard-bearer in the reconnaissance column at the Victory Parade.

- 1. Scientific archive of the Institute of Russian History RAS. Fund 2. Section 4. Op. 1. D. 2643.

- 2. Karpov V.V. The Big Life. Moscow, 2009. Cited from: https://thelib.ru/books/vladimir_karpov/bolshaya_zhizn-read.html.

- 3. Scientific archive of the Institute of Russian History, Russian Academy of Sciences. Fund 2. Section 11. Op. 1. D. 574. Photo of Hero of the Soviet Union V.V. Karpov.

- 4. Karpov V.V. The Great Life. Moscow, 2009. Cited from: https://thelib.ru/books/vladimir_karpov/bolshaya_zhizn-read.html.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Scientific archive of the IRI RAS. F. 2. Section. 4. Op. 1. D. 2643. L. 1.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. Karpov V.V. The Great Life. Moscow, 2009. Cited from: https://thelib.ru/books/vladimir_karpov/bolshaya_zhizn-read.html.

- 9. Ibid. The icebreaker steamship Georgy Sedov with captain K.S. Badigin drifted in the ice of the Arctic Ocean for 812 days from October 1937.

- 10. Karpov V.V. The Great Life. Moscow, 2009. Cited from: https://thelib.ru/books/vladimir_karpov/bolshaya_zhizn-read.html.

- 11. Scientific archive of the IRI RAS. F. 2. Section. 4. Op. 1. D. 2643. L. 8.

- 12. Ibid. L. 9.

- 13. Karpov V.V. The Great Life. Moscow, 2009. Cited from: https://thelib.ru/books/vladimir_karpov/bolshaya_zhizn-read.html.

- 14. Scientific archive of the IRI RAS. F. 2. Section. 4. Op. 1. D. 2643. L. 2-3.

- 15. Ibid. L. 3.

- 16. Kortunov, Aleksey Kirillovich (1907-1973) – Colonel, Hero of the Soviet Union (1945), in 1955-1957 Minister of Construction of Oil Industry Enterprises of the USSR, in 1965-1972 Minister of Gas Industry of the USSR, in 1972-1973 Minister of Construction of Oil and Gas Industry Enterprises of the USSR.

- 17. TsAMO. F. 33. Op. 793756. Unit. hr. 20. N entry 150013362 // https://podvignaroda.ru/?#id=150013362&tab=navDetailDocument.

- 18. Scientific archive of the IRI RAS. F. 2. Section. 4. Op. 1. D. 2643. L. 7.

- 19. Ibid.

Comments